Over the next couple of weeks, leading up to the Hazelhurst exhibition, I am going to be writing a series that shares some of the stories of making and thinking behind the Topologies of Memory quilt. There are quite a few, as it took five months to make.

Maps & Memory

Topology refers to the study of a particular place, specifically the history of a region as indicated by its physical features, such as mountains and rivers ( taken from the Merriam-Webster Dictionary).

The Topology of Memory quilt has obvious references to mapping and the landscape. In a way my references to mapping points not only to the physical location of personal memories, but also the act of understanding the workings of memory. I cannot claim to have a particularly ‘good’ memory, and I’m definitely not one to win awards for navigation. Perhaps this is why these fields hold my interest and conjure questions for me.

Birds Eye View

My backyard studio.

A little while before I started work the quilt, I had attended a two day workshop with visiting Ontario-based textile artist Dorothy Caldwell. Do you know her work? You must have a look.

To be able to spend such an expanse of time upon mark-making without over-thinking things was joyful and freeing. Dorothy created a space where creative tasks could be completed slowly and intuitively. One of the exercises saw us painting freely with a very long brush (almost as tall as a broom) while standing, across large pieces of watercolour paper. In my textile work things tend to be on the micro-to-small scale. Getting large was of huge benefit to the new work I wanted to do with the quilt, which is my biggest to date - 160 x 253cm to be exact. And that is the shrunken size… more about that in stories to come.

So this process of putting down expansive brushstrokes onto paper led me to setting up camp one warm day under the backyard clothes line. I had an aerial-photograph of my family’s property that is the home to many of my childhood memories, and a few google-maps that I’d printed out of the area. I wanted to translate these birds-eye-view documents with a loose painterly line. Dorothy’s technique was perfect for this.

Maps and their marks provide a visual cornucopia for me to draw upon in much of my work. The family farm is literally a patchwork of paddocks, crops, dams and roads. During canola season, fields turn an iridescent yellow. I spoke once to my Pom-Pom (grandfather) about how they originally decided upon the division of the land for farming. He told me they would usually build a house at a high-point, then work from there as the epicenter, slowly expanding out.

It makes me wonder about the families living on the land before this happened, how very shocking it would have been to the original owners to find trees suddenly absent and sacred places no longer. My mum has mentioned she felt there were certain places on the property that she sensed had spiritual qualities as a child. The indigenous history of the area is something I’d like to be more knowledgeable on and I hope in the future to know more about the Wiradjuri people, their history and culture.

Mapping Memory

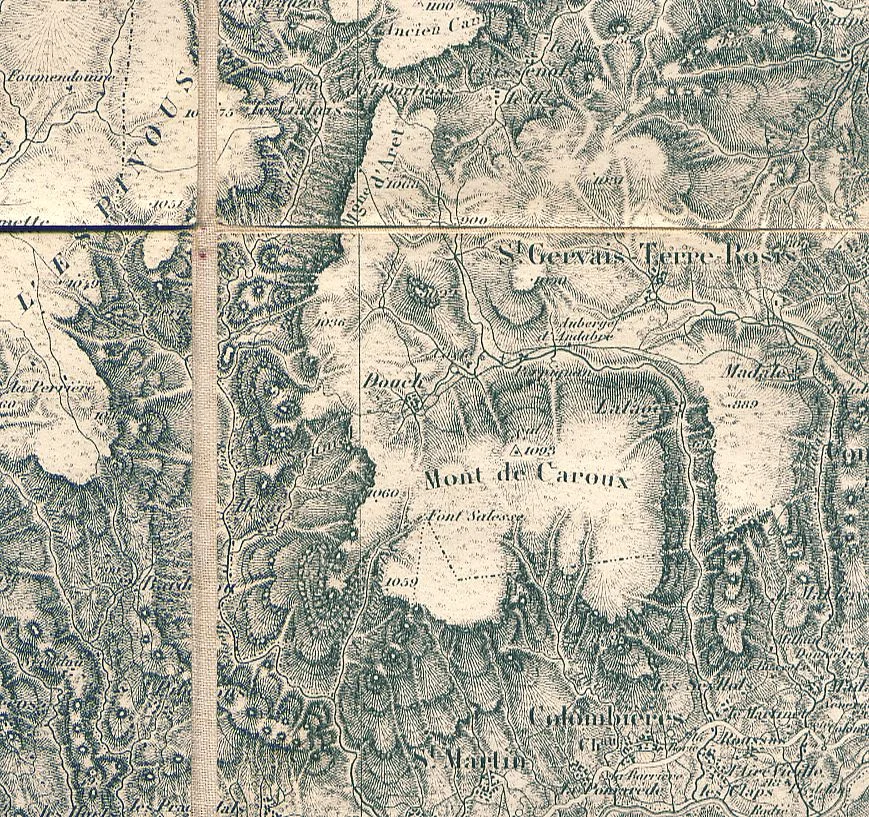

Image: Hachures: A Lost Cartographic Art, The Basement Geographer

Other than literal maps, I’ve been thinking about the mapping of memory and how much we still don’t know about how our minds operate. Ever since listening to this Radio National episode, I’ve been meaning to read more on the man known as HM. As a teenager, he was given a lobotomy in attempt to cure his epilepsy, leaving him with no capacity for memory. He assisted scientists for more than fifty years to understand the way memory works. These ‘unknowns’ leave room to creatively explore the field - imagination and new perspectives have space to breathe until scientists come up with a final map. Perhaps this is why artists, writers, musicians, dancers, actors and poets continue to create art around memory? It’s a fertile field of possibility.

The physical marks of maps are also a world of inspiration for my work. I’ve been particularly interested in the early cartographic technique of hachures. The Basement Geographer shares more:

"Hachures are small strokes that depict slope orientation while conveying the sense of steepness. Hachures are subjectively drawn; there is no number or value attached to them. It is up to the cartographer to drawn them in as he/she best feels would best represent the terrain. Really, it’s an illustration placed on top of a map."

I feel this is how I tend to work within my textiles - stitch lines indicates an idea lying underneath, but it is never an exact reproduction of facts. Similar to memory. The hand lends a beautiful imperfection to my translation of concepts. Julie Paterson’s Imperfect Manifesto is a must read for this kind of thing. (By the way, I’m proud to be mentioned in her beautiful Cloth Book. Look for the Cloth Dollies, if you have a copy).

Next week’s story

I’ll share some of my thoughts on techniques and process, and how I use both to create a sense of time.

I’d love to hear any of your questions or comments. Thanks for reading!

You may have noticed I haven’t revealed a proper full-scale photograph of the quilt… I’m holding off until the exhibition opens… I don’t want to give away the ending too early!